The Legend of Odisho

Some months ago my hairdresser asked me, “So what’s the deal with the Middle East?” It’s a good question. In the twentieth century, a school of anthropologists tried to present an answer: Middle Eastern cultures revolve around honor and shame, whereas Western cultures revolve around guilt and trust.1 This idea has many critics and is highly contested, and I'm not here to litigate it. Rather, I'm here to show what it means: what does an honor-and-shame world feel like from the inside? What kinds of actions earn status, and what kinds invite humiliation?

I want to approach that question through a set of folk songs about Odisho, a semi-legendary nineteenth-century figure from the lawless highland frontiers of upper Mesopotamia, and probably a composite of several men who shared the name. In these songs, Odisho becomes a hero less because he is chivalrous than because he is dangerous: powerful, feared, and capable of violence. It hints at the social currency of low-trust worlds: how order is maintained when courts, contracts, and police are absent or irrelevant. This essay walks through that logic to show what honor and shame reveal as a moral system distinct from the modern Western one.

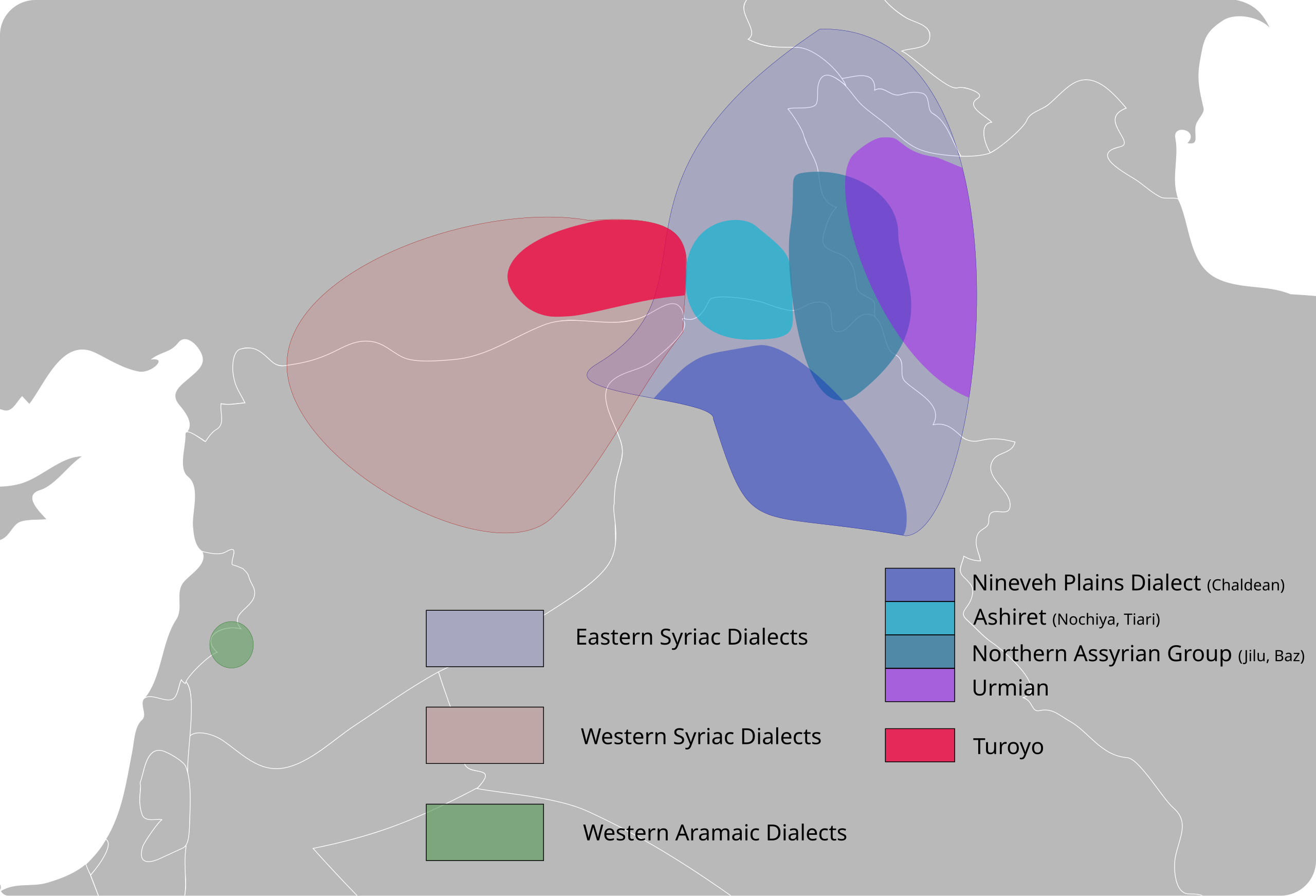

The Assyrians

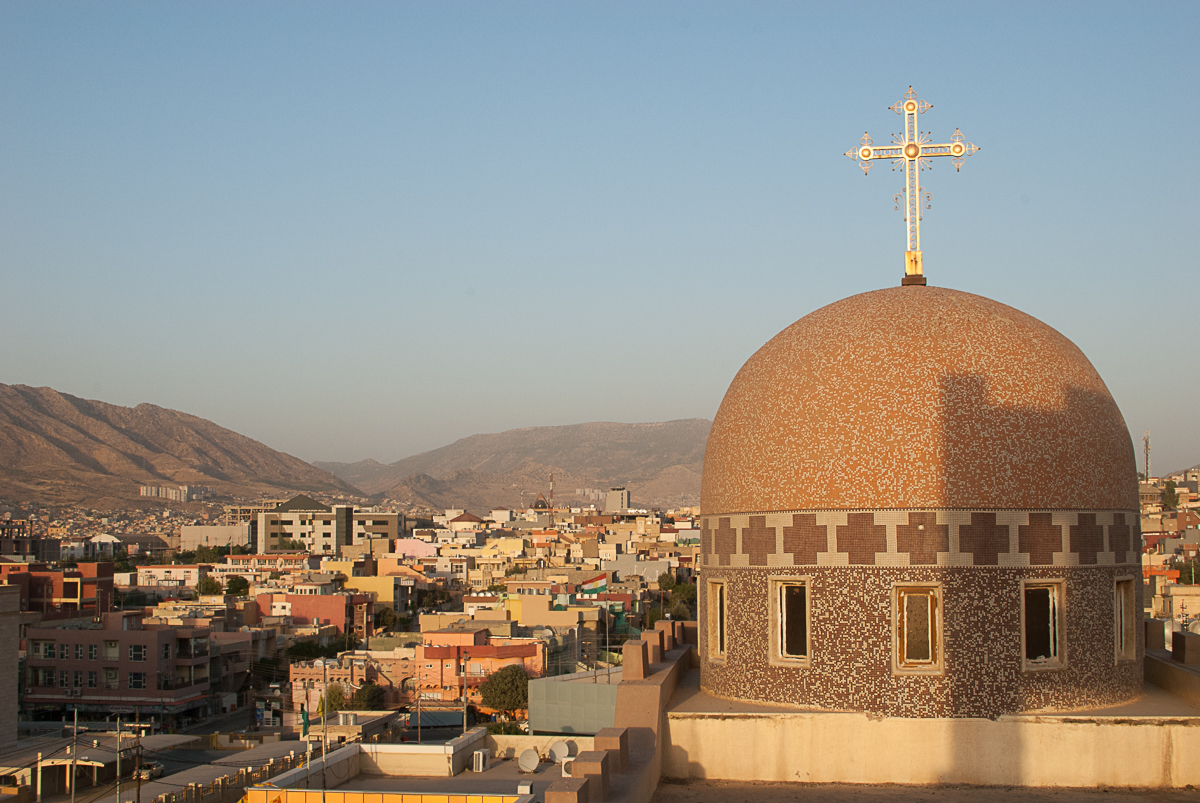

First, we need to set the scene. Our story begins in the mountainous borderlands where Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran meet. In these highlands, there lives a small nation of Assyrians, who practice Christianity and speak Aramaic.2 For centuries they lived here alongside Armenians, Kurds, Yazidis, and Turkmen. You may know some famous Assyrians today like Patrick Bet-David or Mar Mari Emmanuel.

Image credits: Wikipedia (Assyrians, Mar Mari), Integrity Marketing Group (PBD), Mesopotamia Heritage (Church)

The Story of Odisho

Some time around 1820, there was an Assyrian named Odisho.3 This Odisho was from the Tiari tribe in Hakkari, a particularly mountainous region known among Assyrians for its warrior traditions. According to the story, Odisho, or in some versions his uncle, is taking apples to market when a group of Kurds stops him and demands he pay the gzitha.

The gzitha, cognate with the Arabic jizya, was the tax that non-Muslims paid to their Muslim rulers in exchange for protection. In theory, a legal arrangement. In practice, this was often a shakedown: armed men stopping you on the road and demanding payment simply because you were Christian. Though outnumbered, Odisho decides he doesn't want to play along, pulls out his gun, and starts blasting. A modern song recounts:4

My guns hidden under my robes, My dagger clasped upon my side, I killed twenty-six. I am Odisho.

When he runs out of bullets, the story says he switches to his dagger. Details vary from telling to telling, but the traditions converge on the same claim: Odisho kills twenty-six tribesmen singlehandedly.

Odisho in Assyrian Memory

Assyrians have many songs celebrating figures like Odisho: men who refused humiliation, defended themselves, and fought against impossible odds. As with many folk heroes, Odisho is probably a composite. We know of distinct heroic figures like Odisho of Be Bareta, Odisho of Be Elia, and others; it is also a common name in the Assyrian Church of the East. But the songs and folktales repeat the same arc, one that fits neatly within Assyrian memory. Usually, a Christian underdog confronts a stronger Muslim adversary, often endures extortion and threat, and then answers with defiance and violence. Whatever one's cultural vantage point, these are war songs. They express a survival strategy: you may outnumber us, but you'll pay for trying to extort us.

Odisho in Kurdish Memory

Ah, but there are Kurdish songs about Odisho too. Given that he kills so many Kurds in the Assyrian versions, you might expect Kurdish tradition to curse him, or at least forget him. Instead, it does something stranger: Kurdish songs remember Odisho, and not as a villain. They lionize him as a formidable warrior, known in Kurdish as Evdîşo:5

Uncle Evdîşo, the Tiari valley is narrow. Oh Christian, the Tiari valley is narrow. Uncle Evdîşo, his musket makes no sound. Oh Christian, his musket makes no sound. Uncle Evdîşo, Evdîşo is kith and kin. Oh Christian, Evdîşo is kith and kin. Uncle Evdîşo, he fought well on the high slopes. Oh Christian, he fought well on the high slopes.6

So, the most famous Assyrian in Kurdish folk memory is famous because he killed a lot of Kurds.

This is hard for Westerners to process. We do honor worthy enemies: Rommel, Saladin, the samurai. But we honor them for their chivalry, their honesty, their adherence to codes of fair play. We admire Saladin because he was merciful and kept his word, not because he killed a lot of Christians. We do not celebrate outsiders who kill people while acting outside the bounds of lawful authority.

Remember, from the Kurdish perspective, Odisho killed men who, in the Islamic moral-legal framework of sharia law, were simply collecting what was owed. Why?

One answer: the songs don't celebrate Odisho as a friend. They celebrate him as a worthy enemy, based not on chivalry, but martial prowess. In honor cultures, you gain honor by defeating powerful opponents; therefore your opponents must be honored. Conversely, if someone is weaker than you, you face no cost for exploiting them. In historical memory, Kurds tend to paint themselves as nomadic warriors living amongst a docile Christian peasantry. Kurds refer to local Christians with terms like fileh ("peasant"), which Assyrians and Armenians read as a sneer.7

And this is where it gets dark. In the Assyrian telling, the Kurds who stop Odisho aren't warriors meeting him in battle. They are warriors demanding tribute from peasants. They are the strong exploiting the weak, until they discover he isn't so weak. Once they find out he's dangerous, he's worthy of respect.

Honor Cultures

Odisho illustrates an honor logic at its clearest: respect is earned through demonstrated strength. In a low-trust world you can try being peaceful, but peace reads as an offer only if others expect restraint to be reciprocated. When that expectation collapses, restraint can look like submission.

You see the same deterrence logic in American prison culture. When formal protection is weak and predation is constant, “respect” is not admiration; it is the price others pay to avoid testing you. Let someone take your snack and you set a precedent for extortion. Fight back and you communicate something simple: the cost of exploiting you is high. In that environment, violence becomes a kind of social grammar. Harm implies strength; strength commands respect.

This is where honor worlds collide with modern Western instincts. In a high-trust setting, we treat conciliation as virtue and compromise as maturity. In a low-trust setting, an olive branch can read as weakness, an invitation to push further. The instincts are adaptive where law is absent: a survival tactic for making strangers predictable. But they are corrosive to the institutions that assume good faith: contracts and courts, treaties and markets, even democracies. Those systems only function when people believe that cooperation will be reciprocated, and that compromise is not surrender.

The Etiology of Honor Cultures

Where does this honor system come from? The short answer is that honor cultures are a kind of survival strategy. In remote frontier zones where the state is weak and raising livestock is essential for survival, a few bandits might steal your whole flock in the night. To survive, you have to demonstrate that you're too dangerous to prey upon. Odisho's homeland of Hakkari was one such place:

In this setting, alliances between non-clan members are hard, because you can't quite trust anyone. There's a common saying in the region, found in Neo-Aramaic and other languages: Ono w aḥuni cal u abro d cammi, ono w u abro d cammi cal u nuxroyo: "I and my brother against my cousin, I and my cousin against the outsider." Genetics, not voluntary agreement, produces cooperation. Loyalties are nested and situational. There is no universal trust, only shifting alliances based on kinship and threat.

What This Tells Us

If you grew up in a high-trust society, Odisho is hard to read. Our moral reflex is to ask whether he was morally right, whether the tax collectors were legitimate, whether the violence was proportionate. Those questions assume a world in which legitimacy is widely recognized, disputes can be appealed, and restraint will usually be reciprocated. Odisho comes from a world where those assumptions fail. There, respect is more about deterrence than admiration. It means other people decide you are too costly to prey on.

That logic helps explain why Kurdish songs can remember Odisho without loving him. They honor him the way prison culture honors a dangerous man: not because he is good, but because he is formidable. In an honor-and-shame equilibrium, your enemy must be worthy, otherwise defeating him is not glory. If someone is weak, exploiting him is not shameful; it is normal, even expected, until it becomes expensive.

None of this is uniquely “Middle Eastern,” and it is certainly not the only moral system operating there. Imperial urban centers like the Mamluk Cairo, Ottoman Constantinople built administrative bureaucracies with courts, markets, and archives that look more like the high-trust world. But the Near East has repeatedly contained strategically important zones where state power thins out: mountains, deserts, steppe corridors, places with difficult terrain, mobile populations, and porous borders. In those margins, the honor equilibrium reasserts itself because it works: it is a cheap substitute for policing and a brutally effective way to make strangers predictable.

This is where geography matters. European powers like France or Castille spent centuries pressed against other organized states; competition pushed institutions toward standing armies, taxation systems, and bureaucracies that could project authority outward. By contrast, many Near Eastern polities repeatedly confronted frontiers that were not simply rival states, but spaces that were hard to govern at all: Sinai, the steppe, the Saharan and Arabian deserts, highland belts like the Caucasus or Zagros. The result is a recurring historical motifs: ordered centers frustratedly trying to pacify unruly frontiers; frontiers raiding centers; frontier nomads founding dynasties, settling down, and, over time, becoming “civilized” rulers themselves.

You can describe that without celebrating it. Adaptations can be intelligible and still be ugly. A world in which travelers get shaken down on roads, in which conciliation reads as weakness, in which dignity is purchased through violence, is a worse world by almost any measure that matters: safety, freedom, prosperity, the capacity for voluntary cooperation. Honor cultures are not primitive; they are rational responses to lawlessness. But they are also corrosive to the institutions like contracts, courts, and markets that make strangers less dangerous.

So if someone asks, “What’s the deal with the Middle East?”, you might start with Odisho: a man who took apples to market and became a legend in two languages, not because he was virtuous, but because he proved he was not safe to exploit.

Footnotes

-

Anthropologists sometimes speak of a "guilt-shame-fear" spectrum of cultures. Guilt cultures (common in the modern West) emphasize internal conscience and personal responsibility before universal moral standards. Shame cultures (common in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and East Asia) emphasize external reputation and how one is perceived by the community. Fear cultures (common in animist societies) emphasize spiritual forces and taboos. The framework originates with Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946) and was developed by missiologists like Eugene Nida and Roland Muller. Richard Nisbett's Culture of Honor (1996) applies similar ideas to the American South. What I'm calling "honor culture" maps roughly onto shame culture, and "trust culture" onto guilt culture. This framework has critics, particularly in Near Eastern studies, who argue it flattens complex societies into stereotypes. That's a fair criticism, but I'm not inventing this framing out of thin air; it has real scholarly weight behind it and resonates with many people from these regions. ↩

-

The naming question is contentious. Some prefer "Syriac" (emphasizing the church tradition), "Chaldean" (used by Catholics in communion with Rome), or "Aramean" (emphasizing linguistic heritage). "Assyrian" is common in diaspora communities and emphasizes continuity with ancient Mesopotamia. I use it here as the most widely recognized term in English. ↩

-

Odisho is Neo-Aramaic for "servant of Jesus," from the ancient Aramaic ʿabd Ishoʿ. There are many Assyrians today with Odisho as a first or last name, for example the singer Sonia Odisho. ↩

-

While this story has been related to me by Tiari Assyrians, I wanted to provide a source. We see the twenty-six number here reiterated in Edmon Season's 2006 song Odisho; see the third stanza. Translation is my own from Northeastern Neo-Aramaic. ↩

-

See also "Evdiso" by Xesan Eshed (2025) and another traditional version. ↩

-

This translation is my own, with help from Kurdophones, and is probably deficient. I'm assuming fileyo is a vocative form of fileh (Christian) and that xal û xwarzî has the copula -ye elided to make it "Odisho [is your] uncle and nephew" (i.e. your kith and kin), but this is uncertain. Full Kurdish lyrics may be found here. To my knowledge there has been no scholarly work on this folk song to fall back on. ↩

-

Raffi's novel Jalaleddin (1878), set during the Armenian massacres, depicts this dynamic vividly. In one scene, Kurdish horsemen return from a raid with women's undergarments elevated on their spears as trophies: "the shameless criminal, as a boast of his infamous acts, as a sign of triumph, elevates their undergarments on his spear to show the world that he is guilty of a crime against humanity." When asked where they're going, they answer simply: "Against the infidels." In the same scene, the Kurds compare killing fileh to hunting game. ↩