The Illustrious Dynasty of Šidák

There are only 93 people named Šidák in the Czech Republic today.1 The name itself is unusual—according to Pavel Šidák, it derives from old Czech šied, meaning "old man," which is related to the word for "grey" (as in grey-haired).2 The Šidáks are, essentially, "the grey ones"—or perhaps more poetically, "the elders."

This small family originated in Pardubice in eastern Bohemia. According to family tradition, they were Hussite rebels—followers of Jan Hus in the religious wars that convulsed Bohemia in the 15th century. Whether or not this is literally true, the family seems to have inherited something of that stubborn, principled character. Over the centuries, this lineage, though few in number, produced an unlikely concentration of remarkable people: a world-famous statistician, a leading Croatian historian, anti-communist resistance fighters who endured torture and decades of imprisonment, literary scholars, physicians, and a founding figure in American law and economics.

Contents

- The Three Branches

- The Mathematician: Zbyněk Šidák

- The Resistance Fighters: Zdeněk and Helena

- The Historian: Jaroslav Šidák

- The Literary Scholar: Pavel Šidák

- The Physician: Martin Šidák

- The Jurist: J. Gregory Sidak

- A Family Character

The Three Branches

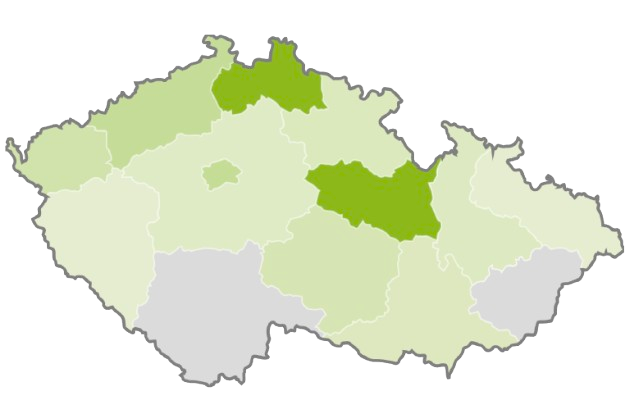

From its East Bohemian heartland, the family dispersed into three main branches: Eastern Bohemia, Vienna, and America.

Pardubice and East Bohemia

The ancestral region. The small towns around Pardubice—Golčův Jeníkov, Zvěstovice, and their surroundings—remained the family's center of gravity. It was here that Zbyněk Šidák, the mathematician, was born in 1933.

Vienna

The Habsburg capital drew many Czechs seeking opportunity in the imperial metropolis. Jaroslav Šidák was born here in 1903 to a Czech family, though he would be raised in Zagreb and become the greatest Croatian historian of his generation. Šidáks remain in Vienna to this day: Kevin Sidak is a researcher in data mining and deep learning at the University of Vienna, while another Christian Sidak works as an energy trader at EconGas GmbH.

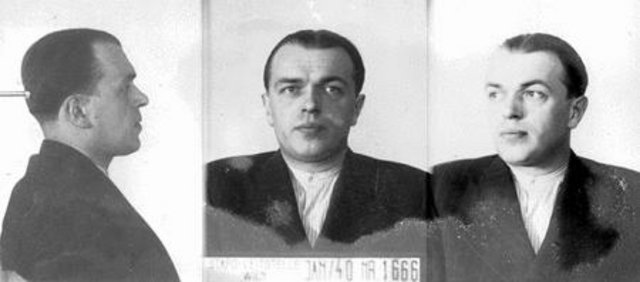

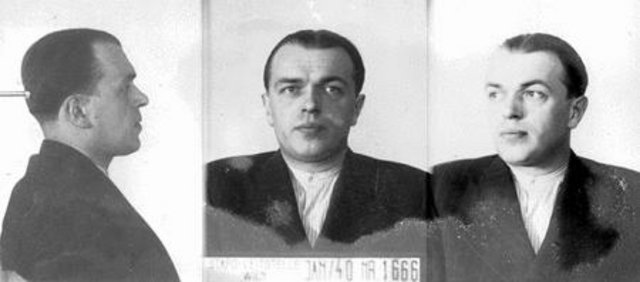

Not all Vienna Šidáks found opportunity. Franz Sidak, a master tailor born on September 22, 1906, was arrested by the Gestapo on January 30, 1940, for staatsfeindliche Betätigung—"anti-state activity." His crime: listening to foreign radio broadcasts. The Gestapo classified him as a Communist and processed him through their identification system—photographed, fingerprinted, filed away. His subsequent fate is not recorded in surviving documents.3

America

There are about 60 Sidaks in America today. The American branch emigrated in 1887 from Zvěstovice—a village near Golčův Jeníkov in northern Vysočina, just over the border from the Pardubice region. This is the same area that produced the mathematician Zbyněk. The proximity suggests these branches were closely related before one crossed the Atlantic.

The family were Protestants who, according to family tradition, left to avoid paying tithes to the Catholic Church. They kept an image of Jan Hus at home. The emigrant, Josef Šidák, had served in the Imperial Army before departing. He and his wife Marie (née Schultz), a German woman, crossed the Atlantic together. Josef never learned English. His son Josef František, who immigrated as an infant, spoke English poorly his whole life. The family can be traced back to Johann Šidák, born in 1810 in Zavratec, just over the border in the Pardubice region.

Upper Silesia?

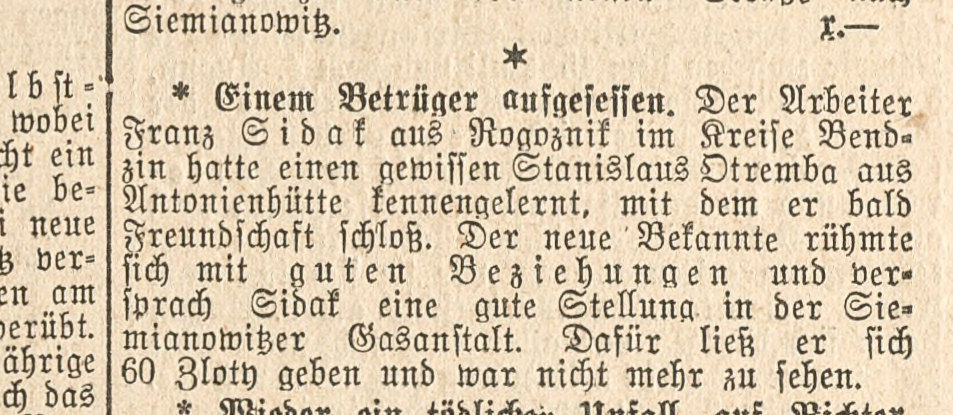

There may also have been Šidáks who crossed the border into Upper Silesia, the historically contested borderland between Bohemia, Poland, and Germany. A 1938 issue of the Oberschlesische Morgenpost records one Franz Sidak of Rogoznik in the Będzin district—though not for any heroic deed. Poor Franz befriended a man named Stanislaus Otremba who promised him a good job at the Siemianowice gas plant. Franz paid him 60 Zloty for the favor, about $1,380 in today's dollars! Otremba was never seen again.4

The Mathematician: Zbyněk Šidák (1933–1999)

Zbyněk Šidák was born on October 24, 1933, in the small East Bohemian town of Golčův Jeníkov. His youth was marked by a congenital heart defect that severely limited his physical activities—a condition that improved only after a successful heart surgery in 1955.5

What he lacked in physical strength, he made up for in intellectual brilliance. He studied mathematical statistics at Charles University in Prague (1951–1956) and spent his entire career at the Mathematical Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, eventually heading the Department of Probability Theory and Mathematical Statistics.

His contributions to statistics are still taught and used today. The Šidák correction—a method for controlling error rates when making multiple statistical comparisons—bears his name and appears in textbooks and statistical software worldwide.6 His 1967 book Theory of Rank Tests, co-authored with Jaroslav Hájek, became a foundational text in nonparametric statistics, reprinted multiple times and translated into Russian. Shortly before his death, he published a revised second edition with P.K. Sen.

For his contributions, Šidák received the Bernard Bolzano Medal, the highest award given by the Czech Academy of Sciences for contributions to mathematics. He held visiting positions at universities across the world: Stockholm (1961), Michigan State (1966–67), Moscow State (1974), the University of California (1986), and the University of North Carolina (1994–95).5

Colleagues remembered him as "an excellent specialist with a clear logical mind, conscientious and accurate in his work"—and as "a quiet, reliable, reserved and honest man with a deep feeling for his family." He married Krista Štěpničková in 1958 and had three children: one daughter and two sons.

He died on November 12, 1999, at age 66.

The Resistance Fighters: Zdeněk and Helena Šidáková

The story of Zdeněk and Helena Šidák reads like a Cold War thriller—except it was real, and the consequences were measured in decades of suffering.7

The War Years

Zdeněk Šidák graduated from a technical high school in Prague in 1944, only to be immediately conscripted for forced labor in Vienna. There, he made contact with Blitz, an Austrian underground resistance group connected to the Czech organization Černý lev (Black Lion) in Prague.

After the assassination attempt on Hitler, something went wrong. Zdeněk was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. Somehow, he was released—and in August 1944, he fled Vienna for Prague, where he hid under a false name until the end of the year. After obtaining more convincing documents, he took a job at the Protectorate radio station while maintaining his resistance connections.

Love at the Radio

After liberation, the Czechoslovak Radio became fateful for both Zdeněk and his future wife. Helena joined the radio staff in 1945.

"I also went to the technical department, where a young blue-eyed technician worked, who besides his job was studying electrical engineering at the technical university," Helena later recalled. "My visits became more frequent, until we grew so close that in February 1946 we became a couple in love, bound for life and death."8

They married on March 12, 1947. Their first son, also named Zdeněk, was born on December 28, 1947. The young family seemed destined for happiness.

Then came February 1948.

The Communist Coup

After the communist takeover, Zdeněk was expelled from both the radio station and his university. Like many young people of his generation, he decided to emigrate. From 1948, he became a collaborator with the American Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), eventually serving as a courier.7

Zdeněk emigrated first, planning to return for his family. Helena, afraid to cross the border with their infant son, stayed behind. Fourteen days after Zdeněk's feigned departure for military service, Helena had to explain to the national committee where her husband was. "I knew well that he was going abroad, but I did not betray him," she later said.

In early 1949, Zdeněk returned from exile as an agent-chodec—a "walking agent"—and organized an escape attempt for his entire family and others. The operation was betrayed. Helena and her infant son were captured and imprisoned in Klatovy. She was soon released, but state security remained on Zdeněk's trail.

Helena traveled to Starý Knín, where Zdeněk was hiding with acquaintances. They didn't know that the secret police had an informant among their friends. Before long, state security agents burst into the cottage. Helena, holding her child, tried to block their way to give Zdeněk time to escape. She was arrested on the spot.

Zdeněk was captured in the Jizera Mountains.

The Sentences

The communist court was merciless:

- Zdeněk Šidák: Life imprisonment

- Helena Šidáková: Twenty years

The brutal interrogations left Helena with permanent health damage. After one session, she couldn't stand on her own. "I must have looked terrible when they dragged me down the long prison corridor," she recalled, "because I remember that the people waiting there to have their protocols written went pale at the sight of me and turned their eyes away."7

Helena was imprisoned in women's prisons in Nový Jičín and Pardubice. She was released in 1955 under an amnesty for mothers with children under ten—an amnesty that President Antonín Zápotocký allegedly announced without Moscow's knowledge.

Fourteen Years

Though imprisoned, Zdeněk several times offered Helena a divorce. She refused to even discuss it.

She waited fourteen years for him—until 1963.

When he was finally released, the torn years could begin to mend. The family was together again. Soon their second son, Martin, was born.

Zdeněk Šidák lived to see the fall of communism in 1989. But in the summer of 1990, he died of a stroke—just months after the regime that had stolen decades of his life finally collapsed. Helena continued to live in Prague's Žižkov district and eventually received official recognition as a member of the Third Resistance under Czech law 262/2011.8

She wrote a book about her experiences with a characteristic title: Přetržené roky—"The Torn Years."

The Historian: Jaroslav Šidák (1903–1986)

Jaroslav Šidák's obituary in the Slavic Review called him "the most outstanding practitioner" of Croatian historiography of the past four decades.9 Born into a Czech family in Vienna in 1903, he was raised in Zagreb and completed all his schooling there, earning his doctorate in 1935 with a thesis on the Bosnian Church.

His scholarly range was extraordinary. Unlike the specialists of modern academia, Šidák approached every field "with the command of a specialist." His research—over two hundred studies and articles—spanned Croatian and South Slavic history from the reign of King Zvonimir in the 11th century to the intellectual development of Stjepan Radić in the 20th.

His work concentrated on four major areas:

Medieval Bosnian neo-Manichaeism — He became the unmatched authority on the mysterious Church of Bosnia, whose exact nature (heretical or merely independent?) scholars still debate.

Baroque Slavism — His studies of Juraj Križanić and Pavao Ritter Vitezović remain the definitive works on these 17th-century pan-Slavic thinkers.

The Croatian National Revival — His distinction between "cultural Illyrianism" and "political Croatism" ended many misconceptions about the 19th-century national awakening.

Croatian Historiography — He was painfully aware that after him, hardly anyone would be capable of writing a comprehensive overview of this field. It is, his obituarist wrote, "a great cultural loss that his time ran out before the completion of this task."9

Beyond his scholarship, Šidák was a man of culture. He was a pianist and edited the journal Jugoslavenski muzičar in the 1920s. He "had the ear for language" and set the aesthetic standard for historical writing in contemporary Croatian.

As editor and founder of Historijski zbornik, the best historical journal in Yugoslavia, he "encouraged the best work available, brooking no interference from any quarter." He had little patience for ideological simplifiers of any stripe. "Jaroslav Šidák prized truth above all else," his obituary concluded, "hence his characteristic stance of wonder that so many subverted this ideal so often."

He died on March 25, 1986, under what his obituarist called "most grievous circumstances." With his passing, Croatian historiography lost not just a scholar but an institution.

The Literary Scholar: Pavel Šidák

Pavel Šidák carries the family's scholarly tradition into the 21st century—and carries in his blood a direct connection to the resistance fighters. He is the grandson of Zdeněk and Helena Šidáková, born to their son who survived his parents' imprisonment as an infant. His paternal family is said to have come from Náchod, in northeastern Bohemia.

A literary theorist at the Institute of Czech Literature of the Czech Academy of Sciences and executive editor of the journal Česká literatura, he earned his Ph.D. in Literary Theory from Charles University in 2008.10

His research focuses on genre theory (genologie), the relationship between literature and folklore, and Czech literary history. His 2018 book Mokře chodí v suše: vodník v české literatuře ("Wet He Walks in Drought: The Water Sprite in Czech Literature") traces the figure of the vodník—the water demon of Czech folklore—through centuries of literary transformation.10

He has also contributed to major collaborative works on Czech samizdat literature, Protectorate-era writing, and 19th-century Czech prose. It was Pavel Šidák who provided the etymology of the family name, tracing it to old Czech šied for "old man."

The Physician: Martin Šidák

Martin Šidák is a physician and medical researcher at Charles University's First Faculty of Medicine and the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care at the Military University Hospital Prague.11

His published research includes studies on trauma care outcomes, echocardiography in intensive care hemodynamic monitoring, the metabolic effects of multiple injuries, and diagnostic techniques for cerebral lesions.11

The Jurist: J. Gregory Sidak

The American branch produced J. Gregory Sidak, a foundational figure in the field of law and economics.

Sidak studied law and economics at Stanford University and became Judge Richard Posner's first law clerk—Posner being one of the most influential legal minds of the 20th century and a founding figure of the law and economics movement.12

His career spans the highest levels of American economic policy and legal scholarship:

- Staff member, President's Council of Economic Advisers

- Deputy General Counsel, Federal Communications Commission

- Academic positions at Yale University, Georgetown University Law Center, and the American Enterprise Institute

- Founder and Chairman of Criterion Economics

In 2005, Sidak became the founding editor of the Journal of Competition Law & Economics, published by Oxford University Press and now the preeminent international journal on antitrust law and economics.12

His writings on antitrust, intellectual property, telecommunications, and constitutional law have been cited by the U.S. Supreme Court, the Supreme Court of Canada, and the European Commission. He has served as an expert witness and court-appointed neutral economic expert across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific.12

A Family Character

What connects a mathematician in Prague, resistance fighters in communist prisons, a historian in Zagreb, literary scholars, physicians, and a law and economics pioneer in America? Perhaps nothing more than coincidence and a shared name from a dialect word for grey.

But looking at their lives, certain qualities recur: intellectual seriousness, moral stubbornness, a willingness to suffer for principle, and an allergy to ideological shortcuts.

The Hussites who may or may not have been their ancestors believed that truth was worth dying for. Six centuries later, their possible descendants seem to have inherited something of that conviction—whether expressed in mathematical rigor, historical accuracy, simple human loyalty, or the pursuit of economic truth in courtrooms around the world.

There are only 93 Šidáks in the Czech Republic. But they have made their mark.

Footnotes

-

"Franz Sidak," Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (DÖW), Gestapo-Opfer database. Photo credit: Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv. ↩

-

"Einem Betrüger aufgesessen," Oberschlesische Morgenpost (Katowice), August 25, 1938. ↩

-

Jan Seidler, Jiří Vondráček, and Ivan Saxl, "The Life and Work of Zbyněk Šidák (1933–1999)," Applications of Mathematics 45, no. 5 (2000): 321–336. ↩ ↩2

-

"Zbyněk Šidák," Wikipedie. ↩

-

Miroslav Šindelář, "Osudných dvě stě metrů," Ministerstvo obrany České republiky, November 15, 2012. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

"Helena Šidáková," Příběhy našich sousedů, Praha 3 (2011/2012), Post Bellum. ↩ ↩2

-

Ivo Banac, "Jaroslav Šidák, 1903–1986," Slavic Review 45, no. 3 (1986): 602–603. ↩ ↩2

-

"PhDr. Pavel Šidák, Ph.D.," Ústav pro českou literaturu AV ČR. ↩ ↩2

-

"J. Gregory Sidak," Criterion Economics, Inc. ↩ ↩2 ↩3