The Greatest Film of All Time

Western audiences have always struggled with The Color of Pomegranates (1969). Sergei Parajanov's meditation on the life of the 18th-century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova defies every expectation we bring to cinema. There is no conventional narrative. Characters do not speak dialogue. Instead, Parajanov presents a sequence of living tableaux—static compositions that feel less like film and more like illuminated manuscripts set into motion.

Most viewers, understandably bewildered, call the film "experimental" or "poetic." But there's a difference between poetic as in vague and poetic as in structured language. Parajanov's film belongs to the latter. He constructed a complete visual and sonic vocabulary—a semiotic system where every object, color, sound, and gesture carries specific, culturally-encoded meaning. The film is difficult not because it lacks meaning, but because it assumes fluency in a language most viewers have never learned.

Rather than describing a plot or recounting events, this essay treats each image and sound as a word in a language Parajanov invented—a language his cultural world already spoke. If you approach the film expecting scenes with characters, you will miss its grammar entirely.

This is not a contrarian take. Filmmakers from Martin Scorsese to Francis Ford Coppola have called The Color of Pomegranates one of the greatest films ever made. It regularly appears on critics' lists of the finest achievements in cinema. What follows is an attempt to explain why—to show what the film is actually doing, and why that makes it not merely beautiful but unprecedented.

This essay is a decoder ring—and here is the measure of Parajanov's genius: everything that follows covers only the first half of the film. The monastic profession that ends Act I occurs at roughly the 35-minute mark of a 73-minute film. What you are about to read documents eight complete motif cycles, four cultural tributaries, and dozens of interlocking symbols, all packed into the density of the opening act alone.

Contents

- The Four Cultural Tributaries

- Strings vs. Bell

- The Pressing Motif

- The Textile-Sexuality Complex

- Windows and Thresholds

- Animals as Soul-States

- The Color Language

- The Shell and the Feather

- The Monastery

- The Pomegranate

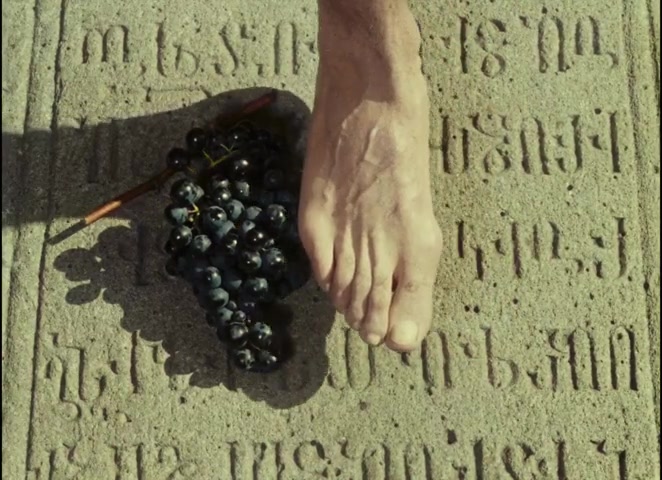

The opening image: a foot pressing grapes. This is not merely visual poetry—it invokes St. Gregory of Narek's theology of suffering as transformation.

The opening image: a foot pressing grapes. This is not merely visual poetry—it invokes St. Gregory of Narek's theology of suffering as transformation.

The Four Cultural Tributaries

Parajanov draws his symbolic vocabulary from four distinct cultural traditions. Each supplies a realm of symbolic meaning—desire, faith, power, and creative life—that Parajanov draws on to make his semiotic system complete.

Sensual Desire (Persian Court): The tar, the kamancha, peacock feathers, turquoise jewelry, coral necklaces,1 porcelain vessels, dancers with mirrors, wine, and the entire tradition of ghazal love poetry. This is the world of luxury, eroticism, and self-expression. Here, the artist can speak.

Sacred Transformation (Armenian Church): Church bells, stone crosses (khachkars), illuminated manuscripts, animal sacrifice (matagh), the monstrance, and the theology of St. Gregory of Narek. This is the world of martyrdom, suffering, and divine grammar. Here, God speaks.

Political Constraint (Georgian Royalty): The hymn Shen Khar Venakhi (addressed to the Virgin Mary as "vineyard"), Georgian bagpipes (Gudastviri), liturgical fans (kshots), antlers, and the golden orb of royal power. This is the world of obligation, ceremony, and silencing. The court that employs the artist also constrains him. Here, the artist is silenced.

Creative Becoming (Domestic/Feminine): Carpets, lacemaking, looms, wool-dyeing, and the abalone shell. Women in this film are almost always shown making things. This is the world of fertility, making, and completion. The young poet seeks in female sexuality what his instincts tell him he lacks: generative power, wholeness. What he cannot find there, Act II's mysticism will ultimately supply.

These four tributaries do not remain separate. Parajanov's genius lies in how he makes them flow together, clash, and transform one another.

The Central Dialectic: Strings vs. Bell

The sonic architecture of The Color of Pomegranates is built on a single recurring conflict: stringed instruments versus the church bell.

The young poet plays for sleeping dye-workers. The plucked strings represent courtly pleasure and the ashough tradition.

The young poet plays for sleeping dye-workers. The plucked strings represent courtly pleasure and the ashough tradition.

What we see is simple enough: around 15 minutes into the film, the adult Sayat-Nova plays music with other musicians on his family's porch. A tar (long-necked lute) plucks a melody—sensuous, associated with the Caucasian ashough (troubadour) tradition that Sayat-Nova belonged to. Then a church bell interrupts. The tar resumes. The bell interrupts again. This pattern repeats four times in rapid succession.

But the resonance goes deeper. This is not incidental sound design. It is the central conflict of Sayat-Nova's life, rendered as sonic combat. Sometimes it is the tar (plucked), sometimes the kamancha (bowed)—both represent the world of courtly art that calls him toward beauty, erotic love, and worldly success. The bell calls him back toward Armenian Christianity—toward God, monasticism, renunciation.

At the midpoint of the film, Sayat-Nova surrenders his kamancha to a bishop and takes monastic vows. It is the kamancha, not the tar, that he gives up—because the kamancha is his instrument, the symbol of his specific artistic identity. But this is not the resolution. The film continues through his monastic life, old age, and death.

The surrender of the kamancha to the bishop marks the renunciation of art.

The surrender of the kamancha to the bishop marks the renunciation of art.

The Pressing Motif: Suffering as Transformation

The opening image of The Color of Pomegranates is a foot pressing grapes. This is not merely visual poetry. It invokes a specific theological idea from St. Gregory of Narek (951–1003), the greatest Armenian mystical poet, who described the suffering of life as being "a grape in a winepress." For Gregory, Christ is the winepresser, and human suffering is the pressure that transforms raw material into something sacred.

In Armenian liturgical tradition, this transformation is literal, not metaphorical. The wine of the Badarak (Divine Liturgy) becomes the actual blood of Christ—"Ays eh aryoon im" ("This is my blood"). The grape must be destroyed to become wine; the wine must be consecrated to become God's blood. Destruction is the precondition of sanctification. When Parajanov opens his film with a foot crushing grapes, he is announcing this theology: only through destruction does the raw material of life become divine.

Parajanov makes this theology visual and then extends it across a complete motif cycle:

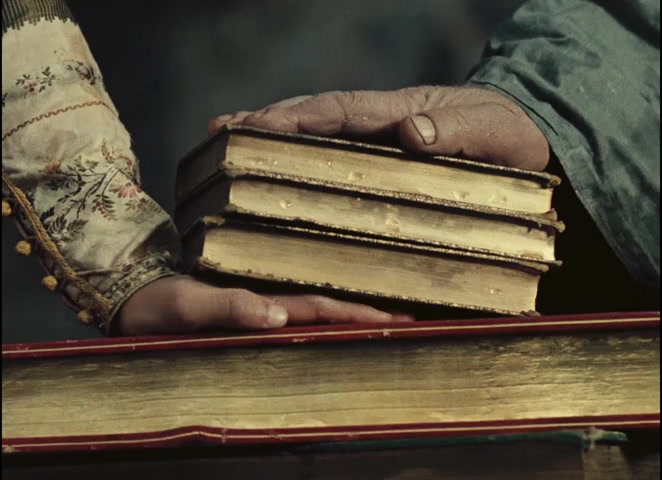

A stone from the church is pressed on books to squeeze out water—evoking the wine/olive press.

A stone from the church is pressed on books to squeeze out water—evoking the wine/olive press.

Grapes → Wine: The opening foot on grapes. Later, monks tread grapes in the monastery.

Books → Manuscripts: A church stone presses down on books to squeeze out water. The raw material of learning is compressed into sacred text.

Books are pressed onto the child Sayat-Nova's hand. His hand will produce poetry.

Books are pressed onto the child Sayat-Nova's hand. His hand will produce poetry.

Hand → Poetry: A monk places books on the child Sayat-Nova's hand, mirroring the winepress image. The child's hand is being pressed; it will produce poetry and music as grapes produce wine.

Rugs → Clean Textiles: Later, feet stamp on carpets to clean them—echoing the foot on grapes.

The theological claim is clear: suffering produces sacred art. The body of the artist is the raw material. Pressure is transformation.

Monks tread grapes in the monastery—the pressing motif returns at the end.

Monks tread grapes in the monastery—the pressing motif returns at the end.

The Textile-Sexuality Complex

Textiles in this film—carpets, lace, wool, looms—carry an explicit symbolic charge. Carpets represent feminine sexuality, creativity, and fertility. They are made exclusively by women. They sway and flow. Water runs over them.

Women washing carpets. Textiles in this film represent feminine creativity and sexuality.

Women washing carpets. Textiles in this film represent feminine creativity and sexuality.

When the child Sayat-Nova stands behind his mother's loom, the warp threads create a screen between them—he is separated from the feminine source.

The child behind his mother's loom. The warp creates a barrier that foreshadows the lace.

The child behind his mother's loom. The warp creates a barrier that foreshadows the lace.

This image foreshadows the central visual motif of the courtship chapter: lace as barrier. Princess Ana, played by the same actress (Sofiko Chiaureli) who plays Sayat-Nova, is constantly shown peering through white lace. The lace is the thing that separates them. She makes it; he cannot cross it.

Princess Ana stares through white lace—the barrier between the lovers.

Princess Ana stares through white lace—the barrier between the lovers.

This is where the grammar becomes visible. The color of the lace tells a story:

- White lace: Innocence, possibility, the beginning of love

- Red lace: Passion, desire, blood

- Black lace: Mourning, loss, death of love

Red lace—passion, the wound of love.

Red lace—passion, the wound of love.

Black lace—mourning, the end.

Black lace—mourning, the end.

Windows and Thresholds

The film incorporates several of Sayat-Nova's most famous poems, and the recurring window imagery is a direct visual quotation. His poem Ashkhares mi panjara e ("My world is a window") meditates on life as a threshold—something we peer through, briefly, before passing on. Parajanov makes this metaphor literal and then multiplies it across the film.

Windows function as liminal spaces—points of access and barrier between worlds. But which worlds depends on context.

In the bathhouse sequence, the child Sayat-Nova peers through windows into both the women's and men's bathhouses, awakening to sexuality. These are erotic windows—points of forbidden seeing.

The child spies through the bathhouse window—awakening to sexuality.

The child spies through the bathhouse window—awakening to sexuality.

In the palace, windows contain the monstrance—the liturgical vessel that holds the consecrated Eucharist. Window + monstrance = God and man gazing at each other. The divine is accessible through this threshold.

The monstrance in the window: God looking at man, and man at God.

The monstrance in the window: God looking at man, and man at God.

But later in the film, the palace windows are filled with black sheep skins. The monstrance is gone. God has departed. The windows that once offered divine access now offer nothing.

The palace windows now hold black sheep skins. The monstrance—the divine presence—is absent.

The palace windows now hold black sheep skins. The monstrance—the divine presence—is absent.

Animals as Soul-States

The Chicken

The white chicken is Sayat-Nova's innocent inner child—helpless, gentle, destined for sacrifice.

The first chicken in the film—being dyed red by faceless dyers.

The first chicken in the film—being dyed red by faceless dyers.

Its first appearance is startling: a white chicken is being dyed red by the hands of wool-dyers. We see only their hands, red with dye like blood. The innocent is being stained.

This connects to matagh, the Armenian tradition of animal sacrifice. On St. George's Day, the family sacrifices a chicken and rubs its blood on the child.2

Chicken blood is rubbed on the child Sayat-Nova during matagh.

Chicken blood is rubbed on the child Sayat-Nova during matagh.

The white chicken becoming red, the innocent child marked with blood—these are the same transformation.

The Peacock

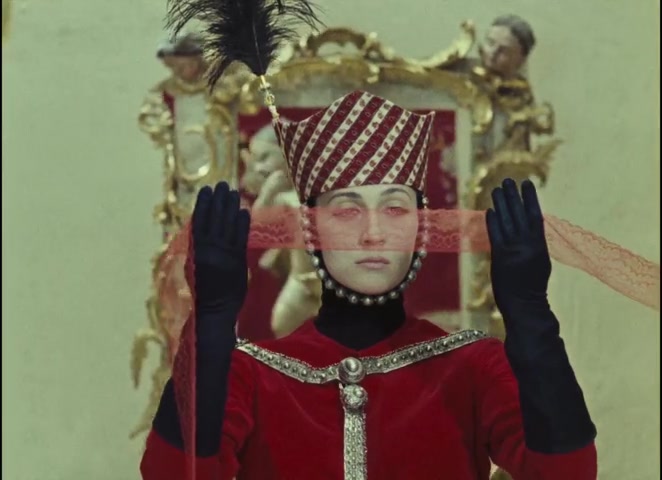

The peacock represents Persian court splendor and the vanity of male sexuality.

An entertainer holds the peacock's tongue—the artist silenced at court.

An entertainer holds the peacock's tongue—the artist silenced at court.

One remarkable image shows a court entertainer holding a peacock while gripping its tongue. The peacock cannot cry out. This is the artist at court: beautiful, displayed, silenced.

Later, Ana wears a peacock feather plume—foreshadowed earlier by a porcelain vase with feathers in the bathhouse. Objects in this film echo across time.

Ana with peacock feather plume—foreshadowed by the bathhouse porcelain.

Ana with peacock feather plume—foreshadowed by the bathhouse porcelain.

The Color Language

Red

Passion, blood, martyrdom, desire, Christ's sacrifice, the love-wound. Dyed hands, dyed wool, red lace, chicken blood, St. George's red cape, the red chukha Sayat-Nova wears when entering the monastery. Red always marks transformation through suffering.

The hand dyed red—stained by desire, marked for art.

The hand dyed red—stained by desire, marked for art.

White

Purity, innocence, poetry, beauty, the beloved. White roses, white chickens, white lace.

White rose in one hand (poetry), candle in the other (faith).

White rose in one hand (poetry), candle in the other (faith).

Black

Mourning, loss, monasticism, death, renunciation. Black cassocks appear swaying in the background early in the film—foreshadowing the monastery. By the end, Sayat-Nova wears them.

Sayat-Nova receives the black cassock—renunciation complete.

Sayat-Nova receives the black cassock—renunciation complete.

Turquoise

Victory, protection, Persian royalty.3 The word comes from Persian pirūz, meaning "victory." Sayat-Nova and Ana both wear turquoise when they are connected; when they remove their turquoise rings, the connection is severed.

Sayat-Nova in turquoise, matching Ana. The color binds them.

Sayat-Nova in turquoise, matching Ana. The color binds them.

The Shell and the Feather

One of the film's most compressed symbolic images shows Sayat-Nova holding an abalone shell in one hand and a peacock feather in the other.

Abalone shell (feminine) and peacock feather (masculine)—sexuality held in balance.

Abalone shell (feminine) and peacock feather (masculine)—sexuality held in balance.

The abalone shell, established earlier in the bathhouse sequence held against a woman's exposed breast, represents feminine beauty and sexuality. The peacock feather represents masculine sexuality and Persian courtly display. By holding both, Sayat-Nova holds masculine and feminine, court and beloved, in precarious balance.

The Monastery: Midpoint, Not Resolution

At the film's midpoint—not its conclusion—Sayat-Nova takes monastic vows. He surrenders his red tunic (desire) and his kamancha (art) and receives the black cassock (renunciation). The film will continue through his monastic life, old age, and death, but this moment marks the crucial turn.

Sayat-Nova enters the monastery in red—he will leave in black.

Sayat-Nova enters the monastery in red—he will leave in black.

But Parajanov does not present this as straightforward spiritual triumph. In one of the film's most striking images, Sayat-Nova stands before the monastery holding an open book (learning, scripture—the only thing he has kept) while monks in front of him furiously devour pomegranates, juice running down their faces, making wet, obscene sounds.

Monks devouring pomegranates. Even in the monastery, desire persists.

Monks devouring pomegranates. Even in the monastery, desire persists.

The message is unmistakable: even here, in the place of renunciation, desire persists. The monks have taken vows, but they are still consumed by sensuality. The pomegranate—symbol of fertility, blood, the seeds of life—cannot be escaped by changing clothes.

The Pomegranate

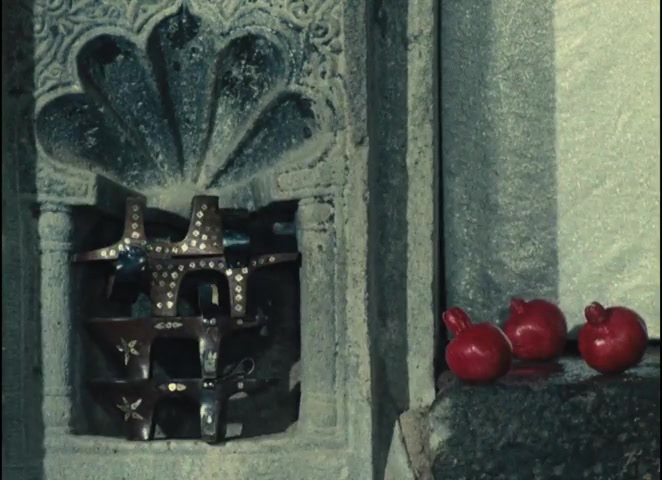

Three pomegranates in a niche during the bathhouse sequence—the first of only two appearances in Act I.

Three pomegranates in a niche during the bathhouse sequence—the first of only two appearances in Act I.

The pomegranate is the title image, yet it appears only twice in all of Act I. The first time: here, three pomegranates rest in a niche during the bathhouse sequence, as Sayat-Nova awakens to sexuality. The second time: monks devour them outside the monastery (shown above), juice running down their faces. That's it. Sexual awakening and monastic renunciation—the fruit of desire bookends the entire arc.

This restraint is itself meaningful. The pomegranate does not need to appear constantly because it operates through every other symbol in the film, accumulating meaning as it goes.

Pressing and transformation: Pomegranates stain. Their juice dyes fabric, skin, stone. They participate in the pressing motif alongside grapes—raw material crushed into something new. When the monks devour pomegranates with juice running down their faces, they are being stained by desire even in renunciation.

Color: The pomegranate is violently red. It operates within the film's color language as blood, passion, martyrdom, and the wound of love.

Armenian national symbol: The pomegranate has represented Armenia for centuries, appearing on khachkars, in manuscript illuminations, and throughout Armenian decorative arts. A film about a national poet-saint naturally centers a national symbol.

The forbidden fruit: Professor James Russell, the Harvard Armenologist, once remarked to me that in Armenian tradition the fruit of the Garden of Eden is understood to be a pomegranate rather than an apple. The manuscript evidence is not always explicit, and what I have been able to find in textual sources is somewhat inconclusive. Still, it is my understanding that in classical Armenian visual culture the pomegranate often occupies this role.

If so, the symbolism sharpens considerably. The pomegranate becomes the fruit of knowledge, temptation, and sensual abundance. To eat it is not merely to disobey, but to awaken—to taste richness, plurality, and desire. To eat it is to fall.

Adam and Eve with the serpent. From the Malnazar Bible, Isfahan, 1637–1638—slightly before Sayat Nova’s time. The J. Paul Getty Museum. The fruit itself is ambiguous here. You may judge for yourself.

Adam and Eve with the serpent. From the Malnazar Bible, Isfahan, 1637–1638—slightly before Sayat Nova’s time. The J. Paul Getty Museum. The fruit itself is ambiguous here. You may judge for yourself.

When you see pomegranates in this film—and you will see them constantly—you are seeing all of these meanings at once: Armenian identity, Edenic temptation, the stain of desire, and the press of suffering.

When the church bell interrupts the tar, or white lace turns red, or the kamancha is surrendered, these are not poetic flourishes—they are repeatable meaning-units in a symbolic grammar. Once you attain fluency in that grammar, the film's clarity becomes overwhelming.

A Film to Be Read

The Color of Pomegranates is not a film to be watched. It is a film to be read—decoded symbol by symbol, like an illuminated manuscript brought impossibly to life.

This is why it is the greatest film ever made. Not because it is beautiful (though it is unbearably beautiful). Not because it is "artistic" in some vague sense. But because Parajanov achieved something unprecedented: he created a complete semiotic system for cinema. Every element—visual, sonic, gestural—carries assigned meaning drawn from real cultural traditions. The film is a language.

Most films show us stories. This film requires us to become literate.

The experience of understanding The Color of Pomegranates is unlike anything else in cinema. When the church bell interrupts the tar and you know what that means; when the white lace turns red and you feel the longing; when the kamancha is surrendered to the bishop and you recognize it as the death of art—the film transforms from bewildering opacity into overwhelming clarity.

Sayat-Nova wrote poetry in three languages: Armenian, Georgian, and Azeri. He lived at the crossroads of empires and traditions. Parajanov made a film that is equally polyglot—a work that speaks Persian and Armenian, Christian and courtly, sacred and erotic, all at once.

To watch it without understanding is to hear a symphony as noise.

To watch it with understanding is to witness the greatest visual poem ever committed to celluloid.

A note on interpretation: the readings above are mine, developed through frame-by-frame annotation of the film. Other scholars and viewers will see different patterns, assign different meanings, emphasize different symbols. That is as it should be. A film this rich supports multiple coherent interpretations. What I have tried to offer is not the definitive reading, but a reading—one that makes the film's internal logic visible.

Images extracted from the 1969 Soviet restoration. Timestamps and analysis based on frame-by-frame annotation of the original Armenian title, Նռան գույնը (Nran Guyne).

Footnotes

-

In classical Persian poetry, coral (marjān) was used in comparisons with bright red things—lips, complexion, tulips—and as a metaphor for lips, blood, and bloody tears. Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent's Gazel: "Thy mouth, a casket fair of pearls and rubies, / Thy teeth, pearls, thy lip coral bright resembles." ↩

-

The film also shows an icon of St. George with a rescued boy—not the typical dragon-slaying image, but a lesser-known scene depicting the saint rescuing a Christian child from Arab captivity. See "Who is St. George's Boy?" for the full hagiographic account. ↩

-

For a comprehensive analysis of turquoise symbolism in Iranian culture—including its associations with victory, prestige, and apotropaic power—see Maryam Kolbadinejad, "The Symbolic Meaning of Turquoise in Iranian Culture" (2021). ↩